Obstacles derived from interviews#

Few data standards in place#

Remote sensing has become a common tool for humanitarian actors (Lang et al., 2019), but much humanitarian data must still be collected on the ground. This means data must be sourced from country governments or collected by the actors themselves. In many cases, official government data are collected and stored in formats and schemas that make sense for the country but do not jibe with the standards and processes of humanitarian actors. Without binding international standards, data managers across various institutions apply their own data standards, with varying degrees of enforcement; there are benefits and drawbacks to such flexibility. Strict data standards are problematic as the situation on the ground varies from place to place in data requirements, collection methods, and local capacity. Enforcement of strict standards makes data depositing, collection, and management more difficult, and limits data exchange. However, flexibility makes data sharing and exchange more complicated, requires additional documentation, and make development of tools and methods that leverage such data more complicated. Various organizations have approached this problem in different ways.

UNHCR#

The implementation of the UNHCR data models highlights how flexibility in application of data standards can be beneficial. There is a centralized model, which is developed and maintained in coordination between GIS headquarters and regional and country office staff, however in-country implementations each adapt the data model depending on their needs. The compromise between having individually adapted data models at each site and a single model for all locations was to have a common data model for each country - these are openly available.

IOM#

The GIS team of IOM who maintain the Displacement Tracking Matrix (DTM) collect and disseminate geospatial data about mobility, vulnerabilities, and needs of displaced people and mobile populations, but they also map physical infrastructure. Like UNHCR, they use data standards internally, but have not published their data schemas.

Others#

MSF and ICRC currently work on harmonizing their internal data handling. 510 Global, the geospatial initiative of the Netherlands Red Cross, consult Red Cross Red Crescent societies in other countries in their use of geospatial data. They do not try to enforce a strict data standard, but instead encourage the country societies to develop their own data schemas to foster ownership over their own data and data-handling infrastructure.

Limited awareness for usefulness of geodata#

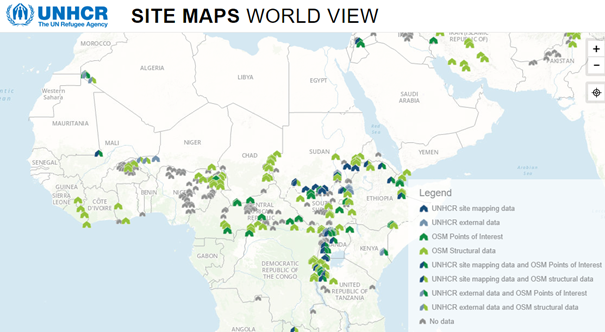

Despite the progress made in recent years to advertise the benefits of geospatial data and analysis, and evangelize the value of collecting and disseminating geolocated data, several interviewees expressed that project leaders and staff are often not aware of the benefits of geospatial data collection and analysis. This is exemplified by the relatively large number of refugee sites which are still not mapped in detail. UNHCR’s geospatial team manages geospatial data of refugee site infrastructure, such as shelters and WASH installations etc. Some of the mapping is done by UNHCR staff into an internal database, some is done by specialized actors like REACH or CartONG, and other data is mapped by volunteers into OSM. The map in Figure 6 displays data availability at a number of refugee camps; for a number of locations, no detailed data are available.

Fig. 5 Overview of UNHCR’s sites of People of Concern, with their mapping status. Grey indicates that no data is available. From https://im.unhcr.org/apps/campmapping/#

While UNHCR has access to satellite images and could organize mapathons to map features that are visible in them, the bottleneck is to map points of interest and their attributes on the ground. This depends on regional and local staff prioritizing the collection of such information. Other interviewees have expressed similar experiences, stating that project managers are not aware of how they can make use of geospatial data: they do not request geospatial information products and cannot state precisely what they need. Therefore, geospatial experts do not know what to deliver to best improve operational, on-the-ground projects. To improve this situation, geospatial products should not be developed for a user, but rather with the user in an iterative loop. Such an agile work procedure is currently also adopted by ESA’s program to develop remote-sensing based information products for global development assistance; example for agile development: Invitation to Tender: “Agile EO information development (GDA-AID): marine environment and blue economy”.

Project-specific requirements make data schema development difficult#

Several interviewees reported that although an estimated 70% of data items to be collected are similar from one project to another, specific requirements make creating a universal data model impractical; three specific examples highlight this problem:

UNHCR adapt a generic data model to each country, so that at least at the level of countries the user does not have to combine different models for an overview analysis. o One example for a complex situation was a fire station, which was manned, but did not have fuel to operate its fire engines. Depending on the actual purpose of the information collection, a simple tag “operational” or “not operational” would not have given sufficient information about the status and options to improve the situation.

The Geo-Enabling Initiative for Monitoring and Supervision (GEMS) supports World Bank projects in mapping and monitoring projects. They similarly report that local data requirements are too detailed and complex to collect in a fixed schema across all projects. Data schemas should also not be too complicated, because users hesitate to use them.

The variations of attributes (tags) in the OpenStreetMap schema also show the difficulty in defining and implementing the needs and requirements of a widespread userbase. Some organizations have defined data schemas, whereas others prefer to allow their geospatial experts to adapt to the given information according to their experience. Data might also be collected differently in different countries due to their own tradition or working procedures. Adapting the data model to these specifications is then a question of identity, and important for local buy-in.

Data collection for specific projects or institutions, not the general community#

Several interviewees pointed out that their mandate is to collect data specifically for the projects or applications under their mandate. This means that data sharing or re-use is not always considered from the onset, and therefore not consequently done. Data then remains with the organization, and other potential users may only know of the existence of the data through personal contacts. This can lead to “data silos” where data from numerous sources have been collected for a specific application, but attention has not been paid to how to make the source information available alongside the results and conclusions.

Data sharing platforms exist, but are not the default#

Although data sharing platforms like HDX and similar domain- or country-specific tools (e.g., Water Points, Healthsites.io, World Bank data hub) are available, they often lack the buy-in from all data contributors. Consequently, the data on these platforms may not be maintained and updated, there is low quality control, and it may be unclear who is responsible for maintenance. For a user it is then better to contact the data provider directly, although that is a higher organizational burden on the requestor and data producer. Another consequence of missing buy-in can be that several platforms with similar uses are being build and maintained (without cross-referencing their data). This means data are often duplicated in many places, without clear attribution, or refence to data timeliness. For example, consider the number of OpenStreetMap extracts found on catalogs like HDX, the Development Data Hub, and EnergyData.info.

Lack of awareness for information management#

Some institutions lack the awareness for the importance of information management. Maintaining data according to a given standard and metadata standard is therefore not enforced; information management is often treated as a technical issue of maintaining computer hardware, rather than focusing on the required business processes and training to ensure uptake of the software and tools.

Data streams vs datasets#

Interviewees from the World Bank pointed out the importance of investing in data streams instead of datasets. As soon as data are purchased, they are, by definition, out of date; while this is not a problem with most analyses, it is an important consideration when make decisions on time and money in data purchases and data collection. It is more important to invest in capacity building, so that data is permanently being updated and improved from authoritative local sources. One important data stream is building up a community of OSM contributors, with the additional advantage that this data is still accessible even in situations of political unrest.

Problems with administrative boundaries and placenames#

Interviewees from UNHCR, IOM, UNFPA, UNDP and ICRC reported that the geographic extent of small administrative units is often difficult to obtain or unreliable. These borders might be not defined properly, are disputed, or their exact definition is not available in digital format, because they might get published only in a gazetteer in written form. This means that information from different sources cannot be combined properly. The SALB project of the UN has the aim to produce officially endorsed administrative units. It is ongoing for over 20 years, with still a lot of work ahead. The Common Operational Datasets are the way OCHA tries to overcome these problems, but they are not available for all countries. UNHCR therefore maintains their own collection of administrative boundaries. Alternative sources for admin boundaries are GADM and geoBoundaries, the outlet of the SALB project. To avoid problems with admin areas, IOM and UNHCR collect data at the level of villages or even finer, so that the aggregation of information to an admin area can be changed if the geographic extent of the admin area changes.